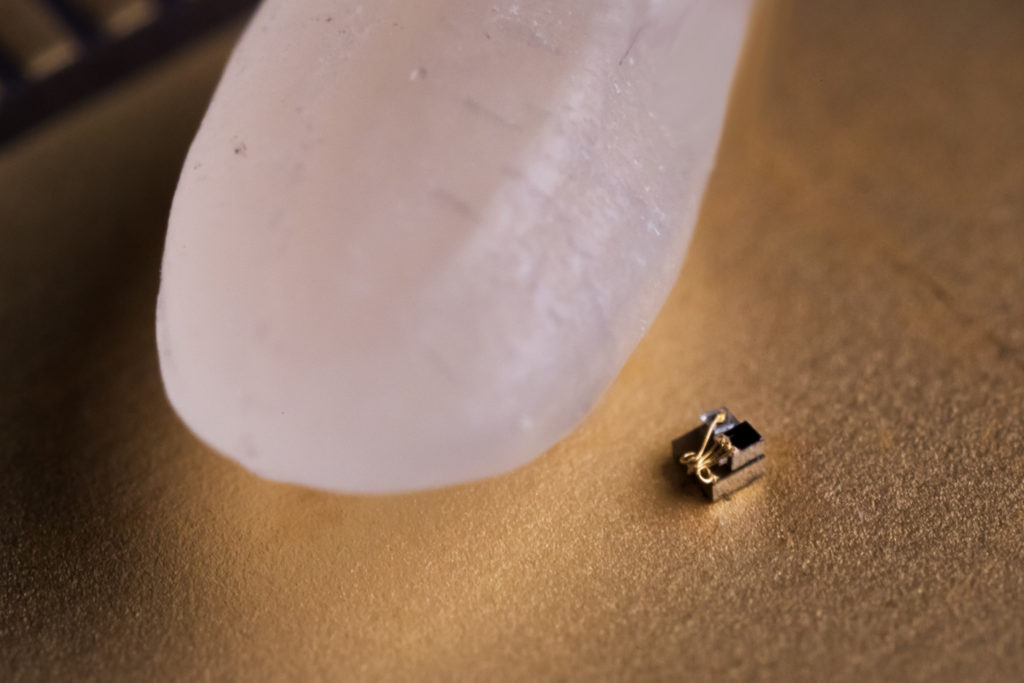

Earlier this year, IBM created a computer they claimed was the smallest in the world. Now there’s a computer that’s even tinier. Researchers at the University of Michigan have developed a temperature sensing device that is just 0.3 millimetres big—or about one-tenth the size of IBM’s device.

The tiny machine is so small that it’s dwarfed by a single grain of rice. Yet, it is fully functional. According to Engadget, the computer is “so sensitive that its transmission LED could instigate currents in its circuits.”

Researchers had some challenges when building the minicomputer, such as how to cut down the effect of light.

“We basically had to invent new ways of approaching circuit design that would be equally low power but could also tolerate light,” explained David Blaauw, a professor of electrical and computer engineering who led the development of the new system alongside Dennis Sylvester, ECE professor, and Jamie Phillips, an Arthur F. Thurnau Professor and ECE professor.

Instead of diodes they used switched capacitors. They also had to battle the usual electrical noise that comes from a device that produces such little power.

The computer is a sensor that can measure tiny areas, such as a bundle of cells in a person’s body. Experts believe tumours may be somewhat warmer than healthy tissue, but they have been unable to prove it. A microcomputer like this may be able to test this theory and in turn, check whether cancer treatment is working.

“Since the temperature sensor is small and biocompatible, we can implant it into a mouse and cancer cells grow around it,” Luker said. “We are using this temperature sensor to investigate variations in temperature within a tumour versus normal tissue and if we can use changes in temperature to determine success or failure of therapy.”

The researchers also believe the device could monitor biochemical processes, diagnosis glaucoma, be used for audio and visual surveillance, and aid in the study of small animals such as snails.

There is some controversy over whether this and IBM’s tiny device are actually computers. Other small computer systems keep programming and data even when they lose power. Michigan and IBM’s computers lose programming and data when powered off.

“We are not sure if they should be called computers or not. It’s more of a matter of opinion whether they have the minimum functionality required,” Blaauw noted.