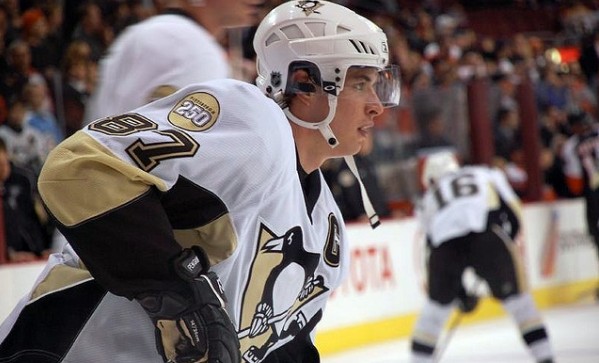

Pray hockey’s Golden Boy is still golden.

Sidney Crosby, the undisputed face of the NHL (and the 2009 Stanley Cup-winning captain of the Pittsburgh Penguins), suffered hits to the head in back-to-back games this January. The second left Crosby with concussion symptoms of dizziness, headaches and loss of focus. He hasn’t played a game since.

Crosby’s concussion provided the crescendo to a swelling chorus of voices calling for the NHL to act on head shots. Although suspensions have lengthened somewhat since then — notably to serial offender Matt Cooke, who is, irony of ironies, Crosby’s teammate — the league’s official line is that distinguishing deliberate from accidental head contact is, basically, impossible.

In short, nothing’s changed.

On March 30, news from the Penguin camp was that Crosby had resumed practicing with the team. Video released last week shows Sid at his magical best — top-notch stickhandling, effortless skating between pylons and a shot so powerful it explodes the goalie’s water bottle. A backhand shot, no less.

The question isn’t whether Crosby will be back on the ice — it’ll happen, either when the 2011 playoffs start tonight (the Pens are in, and in fact have played well without Sid) or at the start of the 2011-12 season this fall. The real question is whether he’ll be the same player.

Few severely concussed NHLers have returned to pre-injury productivity levels. Perhaps the best yardstick for Crosby is previous-gen All-Star and 1995 League MVP Eric Lindros. At age 25, Lindros was, like Crosby is now, the most dominant force on the ice. Five years and eight concussions later, when he still should have been in his prime, Lindros was effectively finished as a player.

The obvious reason that brain trauma might hinder performance is simply that the brain doesn’t function as well. Concussed players often say things “seem to move slower” during recovery. Perceptual and motor skills are impaired, and the effectiveness of the player is reduced.

A less obvious reason is that the player might lose his “edge” — his willingness to compete as hard as he did pre-injury.

Unlike in the Lindros era, it is common knowledge now that past brain trauma increases the susceptibility to future brain trauma. Take All-Star Marc Savard, whose third concussion three months ago — which looks like it might have ended his career — was suffered as a result of being checked into the boards without any head contact. (His first and most severe concussion was delivered by — anyone see this coming? — Matt Cooke.)

A player with a history of concussions has a choice: either ease up, play it safe and try to avoid another concussion, or go as hard as ever and risk another concussion and a lifetime of depression, irritability and memory loss (the common symptoms of severe post-concussion syndrome).

Although modern teams are careful to ensure players are free of concussion symptoms before they return to the ice (even Major League Baseball has put rudimentary concussion protocols in place this season), the possibility of future concussions always looms. Savard’s example is there for all to see.

If the hockey gods are kind, Sid will play for fifteen more years the way he always has and scribble his name all over the NHL record books. But he could also play cautiously — haunted by the risk of another concussion — and spend the rest of his career as merely an above-average player.

While those inside and outside the hockey world are hoping he returns to his swashbuckling best, there is also the chance Crosby will subconsciously dial his game back a notch rather then risk a lifetime of post-concussion symptoms.

This is the slow-motion tragedy perhaps unfolding before our eyes: the end of the Sidney Crosby we knew.

——————–

Image courtesy of Teka England.