Boxing is, in the words of Joyce Carol Oates, “the cruelest sport.” Consider Joe Frazier, who passed away last Monday of liver cancer. A former world heavyweight champion, when “Smokin’ Joe” died, it was not as a champ, but as an underdog. A footnote. News items dedicated to Frazier’s passing only hemmed in this point, without intention. Per the New York Times: “Finally, in death, it appears Joe Frazier stepped out of Muhammad Ali’s shadow.”

Frazier was a champ — one of the greatest — alongside “The Greatest.” He just wasn’t “The Greatest.” If the coin were flipped and Ali had died last week, Joe Frazier would have been a name on a list. The same goes for George Foreman. Ditto Canadian great George Chuvalo.

In the community of sports there are those who step above: the prodigies. Leaps ahead of the competition, their names include Gretzky, Pelé and Federer. It’s the fan’s dilemma to simultaneously trumpet their glory and, excitedly, await their fall — because there are always others in the wings, super-proficient athletes but simply not prodigies, and they’re called the careerists. Sometimes, sometimes careerists get their shot. And if there’s anything fans like more than a winner with personality, it’s an underdog with heart.

But boxing, more than any other sport, is the domain of underdogs. Historically, its fighters have come from the poorer classes, punching their way up from zip and zilch and nada to million-dollar prize pots. That’s their story; it’s always their story. They’re facing outside chances before the bell even rings.

Frazier was born and raised in the segregated South, a sharecropper’s son. As a young man, he moved to Philadelphia, stole cars and got into trouble. He worked in a meatpacking plant, where he developed a training routine punching beef carcasses and running up the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. If this sounds familiar, Rocky Balboa immortalized that routine (Frazier had a cameo in the Oscar-winning film, but received no credit for his story).

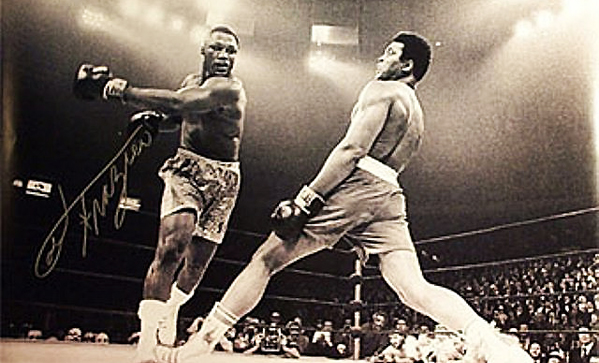

In 1971, Frazier was the undisputed world heavyweight champion (and had been since 1968) — but he had yet to fight The Greatest, who was without a license to box. Little suspecting the cruel irony life held in store, Frazier petitioned Nixon at the White House, to secure Ali’s license. The resulting bout was 1971’s “Fight of the Century.” Both fighters were unbeaten before the match. What history has forgotten is that Frazier won — he walked away with a clean record, taking the title on unanimous decision, and holding it until 1973.

This is how boxing works. To be the best, one has to beat the best. The underdog needs the superstar. Manuel Marquez needs Manny Pacquiao — now, more than ever, having lost a weekend fight to Pacquiao, in a highly contentious split decision. This model bears out in other individual-focussed sports. Take tennis as just one example: Nadal once needed Federer; Djokovic now needs Nadal; Andy Murray needs all three.

We’ll commit a cardinal sin, here, and mention mixed martial arts and boxing in the same space. (After all, we just mentioned tennis.) Which UFC fighter, if he died tomorrow, would compare to a Joe Frazier? With a technical style that is never flashy, Antônio Nogueira has defeated, and fallen to, the big names in heavyweight MMA: Couture, Emelianenko, Filipovic. Quiet, indomitable, and eventually outclassed: How do we figure Nogueira in light of a franchise name like Couture? Is Couture the Ali to Nogueira’s Frazier, or is an MMA Greatest even feasible?

Both at the time and in the end, Ali and Frazier needed one another. Assuringly, it’s been mentioned in the last week that Frazier “was Ali’s foil only if you acknowledge that Ali was his.” Still, his story isn’t the story of a winner, because a champion in another champion’s shadow is still an underdog. That’s how Frazier went in his final 10-count. Call it second place if you want — but why does populist society always have to see it as a distant second?

——————–

Image courtesy of Oytun.

True that!